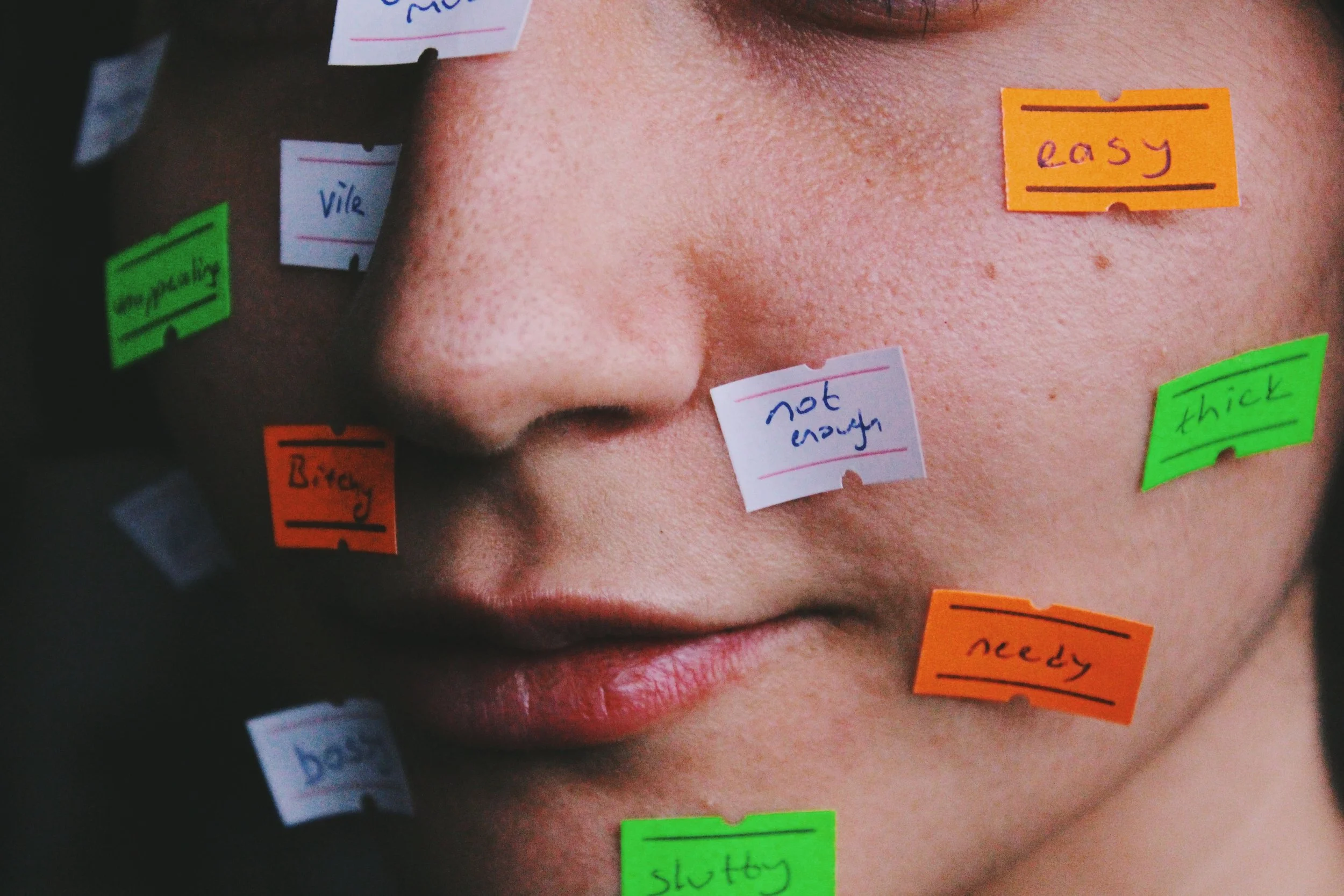

The Curse of Stereotypes

Life is a constant stream of information flooding us from all angles. We are challenged daily to process that information and make sense of the world. With respect to the people we encounter, we ease the challenge by taking shortcuts instead of actually getting to know each person we meet. We simplify people–categorizing them by a myriad of observable, external traits: gender, ethnicity, religion, politics, occupation, race, age, weight, hair color, and clothing. We create stereotypes. Unfortunately, the stereotypes we create are often inaccurate and unfair. Worse yet, we often internalize those stereotypes, making it difficult even to understand ourselves. To the extreme, these stereotypes can become prisons. Fortunately, we can grow and learn and change the stereotypes we create

Now, as an 18-year-old college girl, I reflect on the titles I have been given and the names I have been called. I also reflect on the titles and assumptions I assigned to other people. During the last few years of high school, I realized many perceptions of me, whether they were good or bad, did not accurately describe who I actually am. And, I also see that my tireless striving for success, my continuous desire to prove everyone wrong, has been my struggle to break free from the prison of my own stereotype.

In elementary school, the only noticeable classifications were: If you were in the Talented and Gifted program, you were cool and smart, and if you were very athletic, you were also cool; everyone else didn’t satisfy the two standards. These were the core beliefs of elementary kids. I was a firm believer too. It was a good thing that I took sports very seriously and was also in the TAG program, so I made the cut. I always sat at a full lunch table surrounded by friends, teachers adored me, and at recess the boys let me join their soccer games. There was no talk of wealth, gender, or beauty. Our minds were innocent.

In middle school, it was time to introduce newer, more complex stereotypes. Idolized smart kids became nerds with a preconceived notion that all Asians were in that category. Athletic kids became dumb jocks, pretty girls (specifically blondes) became dumb, having nice things became daddy’s money, and the list went on. Suddenly, I was swimming in labels as implied insults about inherent, unchangeable things. I went from being considered cool and smart to a rich dumb blonde. It was my fault that my parents achieved their own success to provide and obtain the life they wanted. It was my fault for the genetic code I received to have blonde hair instead of brown. The problem I had was not the perception itself. So what if I am called a dumb blonde with daddy’s money. It was that I wasn’t allowed to take it as insulting, or rude, I had to be grateful for the opportunity to be made fun of for coming from wealth, and grateful for being a pretty enough blonde to be considered a brainless barbie. The inability to defend myself, and express the outrageous belief system we middle schoolers had established was what led me to the path I have followed for the past 5 years. The path to prove I am not vacuous or a product of wealth, that I do have substance, goals, and ambition.

Throughout high school I focused on maintaining excellent grades, pushing myself to be in harder classes, all while staying socially relevant. Typically, if you were smart and successful, most people believed you weren’t capable of having a social life, and if you had a social life, then there was no possible way to also be smart. Since I fell into the category of “dumb-blonde” that meant I didn’t really have a place in either. That didn’t stop me from trying. I developed the busiest schedule of my life to keep up. For school, I took two AP courses per semester, joined student council, ran the principal’s committee, and brought a mental health non-profit organization to the school. My social life consisted of attending all the sports games for the school, going out every weekend, and running on the varsity cross country and track teams. I thought being the best of both worlds would rid me of my stereotype by distracting everyone with achievements and fun. All of my activities would prove that I was capable of more than what they assumed of me. Instead, my academic pursuits were swept under the rug, allowing a new stereotype to take shape over my life. Rest easy the dumb blonde, low and behold the ultimate party girl. In an attempt to escape my label, I received an even worse one.

I decided to stop prioritizing my social life, and only focus on my academics, still working towards being considered smart, driven, and successful. When I stopped going out to parties and sporting events, I also lost all of my friends. I didn’t have anyone to go to lunch with, or have a weekend sleepover. So, most of my free time went towards learning more, trying to at least fit in with the smart kids. I continued getting straight A’s in all of my classes and stretched myself to anything that would look good on a college application or resume. Then I applied to 28 different colleges to make absolutely sure I had options for my future. I was focused on my excellence for the future, overwhelmed daily. I pretended not to care that my old best friends were moving on too, finding better, new friends. My world felt so lonely. I didn’t feel like I could grow as a person, and instead, I was lost. I became insecure in my appearance and lack of friends, caring too much about what other people would say. The damage of the stereotypes I was given started to take over my life. I didn’t want to do anything but succeed for the remainder of the academic year and get out to start somewhere brand new. Ultimately, I never ended up connecting with the smart kids since they too believed I was incapable of their successes. It was not my stereotype to fulfill.

After I graduated high school, it felt like a weight had lifted off my shoulders. There were many reasons for this: I was free from the environment of labels, I was going to have the fresh start I’ve always wanted, and though nobody else believed it, I did succeed in high school, so the opportunities I was receiving made it all worth it.

As I reflect back on my high school experience, I realize I was looking at it the wrong way. While I was trying to prove to everyone that my label did not define me, I was also conceptualizing other stereotypes such as the smart kids, and the social extroverts. Even though I believed my stereotype was wrong, I believed that all the other ones I created were true. Not only was I overlooking those labels, but I never considered that people in other categories were going through similar experiences, and that they also don’t fit their stereotypes. I was trying to inject myself into different stereotypes because I thought those people had it so much better. But in reality, nobody wanted to be confined to a single label. Everyone is versatile, with multiple attributes, rather than just one misconception.

The countless hours I spent working to become something I’m not, for a chance at changing how others perceive me, were wasteful. I was so focused on proving to everyone I had more to me than being a dumb blonde or a party girl, that I forgot who I actually was in the process. I was a reflection of what I thought people wanted me to be. It was scary to feel disconnected and lost from myself. But it was also an opportunity to start over with the right mindset this time. I only began this rebuilding 6 months ago, but I have already learned the happiness and freedom I have with the absence of stereotypes. Not to say I have or don’t have them, I just choose not to let it define me anymore. Instead of proving to other people what I can or can’t be, I prove to myself what I want to be.

My personal upbringing resonates strongly with the thematic concerns brought up in literary texts I have read over the past few weeks in class. Specifically, “Only Goodness” by Jhumpa Lahiri and David Brands “The New Whiz Kids,” both explore how identities are shaped and distorted by expectations, labels, and the pressure to fulfill roles assigned by the culture of society. In Lahiri’s story, the main character Sudha battles much of her life managing the burden of expectation. She was the model daughter and successful sibling. However, her attempts to maintain this perfect ideology not only caused strains on her relationships but also blurred her understanding of who she was beyond the perceived obligations.

My personal experience shows how the stereotypes I received when young, became cages I tried outrunning for most of my teenage life. Like Sudha, I valued performing a version of myself that satisfied other people's assumptions, completely forgetting my own truth. Though different experiences, we both felt the emotional cost of letting others perceptions dictate our personal identities. Also, David Brand’s piece adds another layer of comparison from the discussion of how cultural stereotypes shape success, pressure, and self-perception. He especially analyzes how Asian American students are celebrated as naturally gifted “whiz kids”- a term that disregards individuality and assumes success is inherent rather than earned. This stereotype restricts and dehumanizes, not leaving any room for personality and origination. My experience parallels with Brands central claim, that stereotypes, even when framed as a compliment, create expectations people feel compelled to live up to or rebel against. The model minority students, compelled to effortless expectation without room for failure, is similar to my exhaustion of constantly trying to disprove perceptions of me. No matter how hard we try, it will never be enough.

Ultimately, stereotypes simplify people into roles they never chose, and shape environments where individuals are compelled to embody or escape the labels thrown upon them. My own personal experience along with these two other pieces are proof. They are also proof of liberation. Sudha finally took matters into her own hands, by taking a step back from caring about others' expectations. Brand calls attention to seeing students as complex individuals rather than cultural symbols. I realized I no longer want to rewrite other people's perceptions of me. Instead, I want to rediscover and define who I am on my own terms. In reality, all three works show that real growth does not take place when others form their views of you, but when you stop living for those views in the first place. The stereotypes do not define us, we do.